The story of Falotani, Polynesia’s ancient navigation system, is one of the most extraordinary chapters in human history. Long before compasses, GPS, or even written maps, Polynesian navigators crossed the largest ocean on Earth—the Pacific—using only the stars, waves, birds, and the rhythm of nature. These voyages weren’t accidents or myths; they were intentional feats of science, observation, and skill passed down through oral traditions.

Today, the revival of Falotani represents not only the return of a lost art but also the reawakening of cultural pride and indigenous science. This comprehensive guide explores the origins, techniques, decline, and rebirth of this system—and what it reveals about the brilliance of ancient Pacific civilizations.

The Lost Art of Pacific Navigation

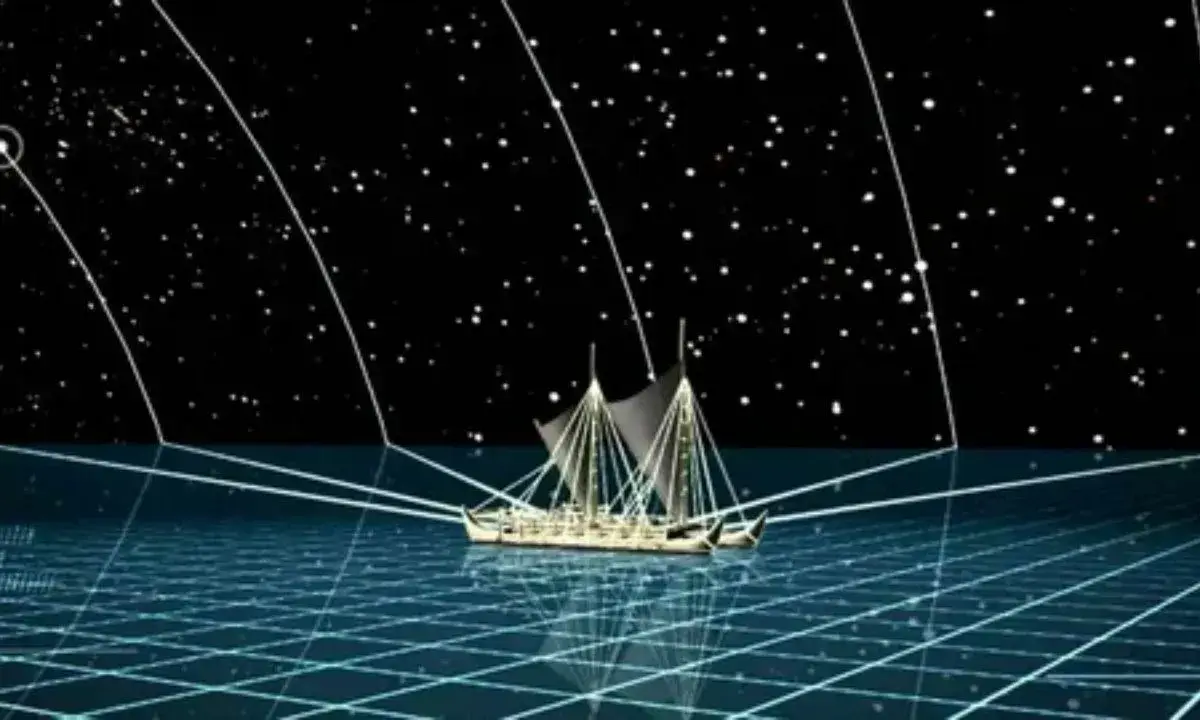

Imagine sailing thousands of miles across open ocean—no compass, no sextant, no modern map. For Polynesian navigators, this was a way of life. Falotani, part of the wider Polynesian wayfinding tradition, relied on deep environmental literacy. Navigators memorized star maps, understood seasonal ocean swells, read cloud formations, and tracked the migration of seabirds to locate land.

This method predates European exploration by centuries. While Western sailors still clung to coastlines, Polynesian voyagers were confidently crossing open ocean between far-flung islands like Hawaii, Tahiti, and New Zealand. Falotani wasn’t superstition—it was empirical science encoded in culture, perfected through generations of observation and testing.

The Historical Context of Falotani

Origins in Ancient Polynesia

Falotani’s roots trace back to the Lapita people, the seafaring ancestors of Polynesians, who began migrating across the Pacific roughly 3,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence—such as pottery fragments found across Melanesia and Micronesia—shows their incredible mobility.

The Lapita carried with them not just tools and food, but an intimate knowledge of the ocean. This knowledge evolved into specialized navigation systems like Falotani. Each island group—Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, and later Hawaii and New Zealand—developed regional variations, but all shared a core reliance on celestial and environmental cues.

In traditional Polynesian society, navigation was sacred. Master navigators were part of elite guilds, often hereditary, who trained for decades. Their teachings were transmitted orally and ritually, never written down. The secrecy wasn’t elitism—it was protection. Knowledge of navigation meant control over life, trade, and survival.

The Golden Age of Pacific Exploration

Between 1000 BCE and 1200 CE, Polynesians achieved one of the greatest migrations in human history—settling nearly every inhabitable island in the Pacific. They reached Hawaii, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), and Aotearoa (New Zealand)—forming the Polynesian Triangle, an area larger than North America.

| Region | Approx. Settlement Period | Distance Traveled (Miles) | Navigational Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tonga & Samoa | 1000–500 BCE | 1,200–2,000 | Crosswinds, reef chains |

| Hawaii | 300–600 CE | 2,400+ | Long open-ocean stretch |

| Rapa Nui | 800–1000 CE | 2,600 | No visible land markers |

| Aotearoa | 900–1200 CE | 1,800 | Cold currents, high latitude |

These voyages required precision. Missing an island by just a few degrees could mean death. Falotani made it possible by using a systematic method—a mental “map” of stars, waves, and environmental patterns memorized and practiced constantly.

The Technical Mechanics of Falotani Navigation

Celestial Navigation Techniques

The stars formed the backbone of the Falotani system. Navigators used a “star compass,” a conceptual tool that mapped rising and setting points of specific stars along the horizon. Each direction corresponded to certain stars, helping sailors maintain consistent headings.

Key Elements of Polynesian Celestial Navigation:

- Star Lines (Kāpehu Whetū) – Specific stars that rose or set in predictable positions, used to maintain course.

- Zenith Stars – Stars passing directly overhead, marking latitude lines unique to each island.

- Seasonal Shifts – Navigators adjusted their routes according to seasonal sky changes.

- Hand Measurements – Fingers and fists were used to gauge angular elevation of stars above the horizon.

Notable stars like Hōkūpa‘a (Polaris), Sirius, and the Pleiades (Matariki) acted as waypoints. Each star path was memorized as part of long chants—oral star maps recited for navigation and ritual.

Reading Ocean Patterns

Falotani also depended on swell dynamics. The Pacific is full of complex, intersecting wave systems generated by distant winds and reflected off islands. Experienced navigators could identify multiple swell directions simultaneously.

Oceanographic Techniques:

- Primary Swell Recognition – Long waves from dominant wind systems provided main directional cues.

- Reflected Swells – Waves bouncing off islands could be detected up to 30–40 miles away.

- Interference Patterns – Cross-swell intersections helped triangulate position.

- Temperature and Color Gradients – Warm or discolored water often indicated land proximity or reefs.

Modern oceanography confirms what ancient navigators knew intuitively: wave energy patterns remain stable over vast distances, making them reliable navigational indicators.

Biological and Ecological Markers

Nature itself was a guidebook. Polynesian navigators read biological signs as part of Falotani:

- Seabirds: Frigatebirds and tropicbirds nest on land and fly out to sea in specific patterns, indicating distance and direction from shore.

- Fish Schools: Certain species, like flying fish or tuna, occur only in nearshore zones.

- Clouds and Reflections: The color and shape of clouds often revealed islands; for instance, a greenish reflection indicated a lagoon.

- Scent and Debris: The smell of vegetation or driftwood on the current could signal nearby land.

This ecological awareness formed part of a holistic worldview—the ocean wasn’t empty space, but a living map of constant signals.

Collapse and Near-Extinction of Falotani Knowledge

Colonial Impact and Suppression

The arrival of Europeans in the Pacific during the 18th century marked the beginning of systemic disruption. Christian missionaries often viewed traditional navigation as pagan superstition. Colonial powers imposed Western navigation methods, and indigenous voyaging was discouraged or even outlawed in some islands.

By the late 19th century, most traditional navigators had been displaced by Western-trained sailors. The oral transmission chain was broken, and the few remaining masters kept their knowledge secret, fearing ridicule or persecution.

Knowledge Bottleneck and Last Masters

By the mid-20th century, traditional wayfinding had nearly vanished. Only a few master navigators remained—most notably Mau Piailug of Satawal Island in Micronesia. Trained in a lineage stretching back centuries, Mau kept the art alive through ritual secrecy.

In 1976, he famously trained the crew of the Hōkūleʻa, a double-hulled canoe built in Hawaii, demonstrating that ancient techniques could still guide a voyage 2,400 miles without instruments. His teachings became the foundation for Falotani’s revival.

The Polynesian Voyaging Renaissance

The Hōkūleʻa and Kealaikahiki Era

The Polynesian Voyaging Society, founded in 1973, launched a movement to rediscover ancestral knowledge. With Mau Piailug’s guidance, they rebuilt traditional canoes and tested Falotani’s accuracy under modern scrutiny.

The 1976 Hōkūleʻa voyage from Hawaii to Tahiti was a triumph—it proved that Polynesians were indeed deliberate navigators, not accidental drifters. Subsequent voyages across the Pacific and beyond revived not just navigation, but cultural confidence across Polynesia.

“Our ancestors sailed intentionally. They knew where they were going. They had maps in their minds, not on paper.” — Nainoa Thompson, master navigator

Re-Certification and Education

Modern Falotani training programs blend tradition with scientific study. Navigation schools in Hawaii, Tahiti, and the Cook Islands teach both star compass training and modern oceanography. Apprentices undergo years of mental and physical conditioning to master:

- Night sky memorization

- Canoe handling in variable conditions

- Non-instrument wayfinding assessments

- Cultural protocols and chants

Certification as a pwo navigator (master navigator) remains a sacred honor—earned, not given.

Modern Applications and Cultural Significance

Scientific Validation of Falotani Knowledge

In recent decades, scientists have tested Falotani’s accuracy. Controlled experiments show traditional navigators can achieve landfall precision within 25–50 miles after multi-week voyages—without instruments.

Oceanographers also confirm that swell reflections can indeed be traced from over 30 miles, validating oral accounts once dismissed as “legend.”

Neuroscientists studying wayfinding find that navigators develop extraordinary spatial memory and pattern-recognition skills comparable to expert pilots or mathematicians.

| Study | Year | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| University of Hawaii Wayfinding Project | 2012 | Traditional methods achieved <2° average heading deviation |

| Oceanography Research, Tahiti | 2016 | Confirmed stable swell reflection zones detectable up to 40 miles |

| Cognitive Science Study (Nature) | 2021 | Navigators show enhanced hippocampal activation linked to spatial mapping |

Cultural Identity and Decolonization

The revival of Falotani is more than historical curiosity—it’s a form of decolonization. For centuries, Western narratives painted Pacific Islanders as passive drifters. Reviving Falotani reclaims their identity as scientists, explorers, and innovators.

Today, the Hōkūleʻa continues to sail globally, promoting indigenous science and ocean stewardship. Falotani is being integrated into school curriculums across Polynesia, teaching children not only how to navigate but how to see the ocean as an interconnected ecosystem.

Case Studies: Falotani in Action

Hōkūleʻa World Voyage (2014–2017)

The canoe circumnavigated the globe, covering 42,000 nautical miles without GPS. The voyage emphasized sustainability and unity through the motto “Mālama Honua”—care for our Earth.

Satawal–Hawaii Knowledge Transfer

Mau Piailug’s mentorship of Hawaiian navigators became a case study in inter-island cultural exchange, leading to the re-establishment of pwo ceremonies across Micronesia and Polynesia.

Marshall Islands Stick Charts

These tactile maps of swell and current patterns parallel Falotani principles. Researchers now use them as analogues for oceanographic modeling and data visualization.

Conclusion: The Continuing Journey

Falotani isn’t just a remnant of the past—it’s a living science that challenges modern assumptions about knowledge and exploration. It proves that navigation can be cognitive, ecological, and spiritual all at once.

As Polynesian voyagers continue to sail, they’re not just retracing ancient routes—they’re navigating toward a future rooted in ancestral intelligence. The rebirth of Falotani is a reminder that science and culture are not separate, and that the ocean still holds lessons written not in ink, but in stars and waves.

Key Takeaways

- Falotani represents one of humanity’s most advanced non-instrument navigation systems.

- Its principles—celestial mapping, wave analysis, and ecological observation—are scientifically valid.

- The system’s revival is both a cultural and intellectual renaissance across the Pacific.

- Falotani connects the ancient past to modern sustainability and identity.

Ember Clark is an expert blogger passionate about cartoons, sharing captivating insights, trends, and stories that bring animation to life for fans worldwide.